Crafting Inner Space: Why Design Matters in Psychedelics

How do we Set the Setting?

Set and setting are widely recognized as critical factors in shaping psychedelic experiences. But you don’t need to sift through countless academic studies or consult therapists to understand their impact. Just ask any recreational user. They’ll tell you that a day in the serene embrace of nature can expand your sense of self just as much as being swept up in the pulse of light and sound on a packed dancefloor can dissolve that self into the collective.

This understanding isn’t new. In his definitive book on the subject, American Trip, Ido Hartogsohn traces the origins of our contemporary understanding of set and setting back to the 1950s, when LSD research first identified “non-drug factors” as key determinants of psychedelic experiences. His work highlights the stark contrast between early studies conducted in sterile hospital rooms, which often led to paranoia and distress, and modern therapeutic settings designed to foster breakthroughs in healing.

Yet despite decades of academic inquiry and lived exploration proving why set and setting matter, little attention has been paid to how to create them effectively. The discussion remains vague, with calls for “comfortable settings” or “non-clinical environments” offering little in the way of structured frameworks or actionable guidance.

So, if we know why these factors are essential, why isn’t there more focus on how they are shaped or interwoven into practice?

Clinical therapy room: Visual representation of the stark, impersonal environments used in early psychotomimetic research.

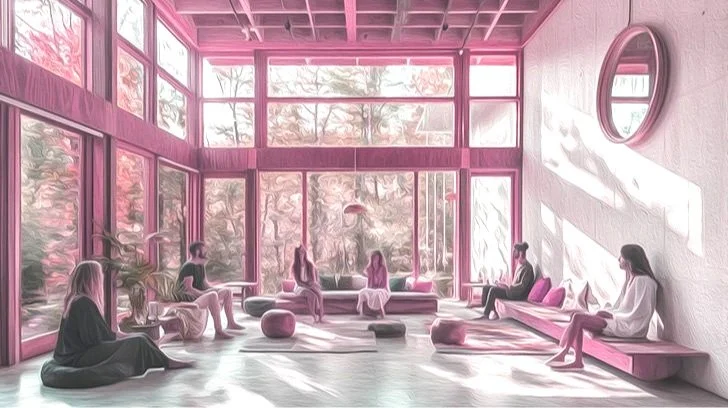

Supportive Healing Space: Warm and welcoming modern therapy room by Field Trip Health (now called Stella). Photo Credit: Field Trip Health

Bridging Set & Setting

The “non-drug factors” that Hartogsohn and other researchers identify - light, sound, spatial layout, and cultural and social contexts - all fall under a discipline rarely acknowledged in psychedelic discourse: design.

Surprisingly, while American Trip mentions “design” 42 times, it rarely refers to it as a discipline. Instead, the word is used in the context of research design or aesthetics in psychedelic-inspired art and fashion rather than the applied practice of shaping environments and experiences. This oversight is repeated across academic literature.

Nearly 70 years after research on therapeutic psychedelics began, and despite overwhelming evidence that set and setting shape outcomes, design remains an afterthought.

Just as set and setting are inextricably linked - our mindset shapes our perception, and our environment shapes our mindset - design operates across both dimensions: mind and environment. Design can physically craft the immediate environment while at the same time empathetically enhance the broader human experience: emotionally, cognitively, sensationally, and culturally.

Design isn’t an afterthought; it’s a vital component of how to craft set and setting, that could significantly enhance psychedelic experiences.

Embracing Design as a Discipline

One of the biggest misconceptions about design, across many fields, not just psychedelics, is that it’s about aesthetics. Many people believe that enhancing a psychedelic space involves adding warm lighting, placing a plant in the corner, and incorporating wellness items such as a salt lamp. They might also suggest hanging something spiritual or psychedelic, like a mandala or an Alex Grey print.

While these elements may enhance the ambiance, this is not design; it’s decoration.

Just as therapy isn’t just about the session itself but the entire process, from preparation to integration, design isn’t just about what a therapy room might look like or the selection of objects it contains. It considers the entire arc of experience and considers the intention of each element how they might work together to foster connection, introspection, or sensory exploration.

Design doesn’t:

Define a room; it orchestrates an experience—from the moment someone enters to how their journey unfolds over time.

Arrange furniture; it shapes interactions, fostering connection, introspection, or sensory exploration.

Solely concerned itself with aesthetics; it shapes perception and utilizes factors like light, color, acoustics, and spatial flow to facilitate altered states of consciousness.

To reduce design to mere decoration is to overlook its true power as a rigorous multidisciplinary practice and a critical problem-solving tool that ensures psychedelic journeys are not just safe but intentional, transformative, and deeply human.

Current approaches to therapeutic & wellness environments:

While therapeutic spaces are evolving with more thoughtfully designed approaches, there’s still immense potential to be even more intentional. By integrating deeper research, design principles, and user experience insights, we can push these environments beyond ‘better’, toward truly transformative

Why Design Belongs in Psychedelics

Psychedelics can be researched up to a point, its effect can be mapped through neuroscience, and the outcomes might be measured in psychological studies, but conventional methods fall short of capturing the full nature of the experience. Psychedelic states are not purely objective; they involve perception, meaning, and an element that defies traditional models of understanding, one that is numinous, tacit, and deeply personal.

Design follows a similar trajectory. Much of it is backed by evidence-based methodologies, principles of ergonomics, sensory perception, and spatial psychology. But beyond that, design, like psychedelics, taps into intuition, perception, empathy and a deeper, almost transcendent understanding of human experience.

This is precisely why design and psychedelics belong together. It brings something to the field that pure scientific research alone cannot.

At its core, design is applied research but with intuition, creativity, and human understanding.

Design translates insights into real-world solutions with a human-centered approach. In fields like psychedelics, designers can apply findings and data from psychologists, neuroscientists, and therapists to create functional, supportive, and transformative experiences and environments.

Here are some speculative scenarios:

Cognitive Effects

Studies suggest that natural light reduces anxiety, but how it’s integrated matters. Designers consider how to integrate light, what angles create the right diffusion, whether indirect sunlight is preferable, or how dynamic lighting can mimic natural cycles, or even design interactive skylights that might enhance a journey. Imagine the possibilities if we pinpoint the optimal color tones or lux levels for the outcome of specific substances, and how this might affect design.

Sensory Perception

Research shows that sound plays a crucial role in guiding psychedelic experiences, but poor acoustics can be disruptive. Designers can ensure that acoustics enhance the experience, whether through curved walls that prevent echoes, materials that absorb disruptive noise, or speaker placement that creates an immersive soundscape. Imagine if we explored the full effects of vibroacoustics, how might this be incorporated into our environments to make them more sensorial?

Physical States

Consider substances like MDMA, which can raise core body temperature. We could design climate-responsive environments that track biometrics and subtly shift temperature to optimize comfort, but design alone can also influence how warmth or coolness is felt - through lighting, materials, airflow, and temperature-responsive surfaces. But imagining a space that can dynamically adapt to the needs of the individual is still pretty cool, though.

These are just a few ways that design can shape the psychedelic experience, but its influence extends beyond the tangible. It also plays a role in emotional, spiritual, social, and psychological dimensions - guiding not only our perception but also how we feel, connect, and integrate the experience.

Research provides us with the what - the measurable effects of light, sound, and space - but design defines the how - how these elements are applied, orchestrated, and adapted to shape the experience.

Without design, the field risks creating environments and experiences that are technically functional but fail to fully support the emotional, psychological, and spiritual dimensions of psychedelic therapy.

Building the Future of Psychedelic Experiences - A Call for Collaboration

In Timothy Leary’s 1967 essay, On Programming the Psychedelic Experience, he suggests that psychedelic journeys could be “programmed” using specific cues like Tibetan yantras, mantras, and incense. While I believe we should honor the sacred wisdom of ancient psychedelic practices, and caution against transposing these rituals without respect or context we should honor the sacred wisdom of ancient psychedelic practices and caution against transposing these rituals without respect or context, Leary’s idea of establishing a framework to reduce harm and promote consistent positive outcomes holds merit.

Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris, a name we should all know in this space and one of the leading researchers in psychedelic science, has reinforced this notion through extensive research. His work demonstrates that context plays an essential role in shaping the effects of these substances, and he has advocated for structured protocols to optimize outcomes.

That said, while science provides a foundation, we know the psychedelic experience is not purely scientific. It is shaped by variables, some tangible, others deeply personal or even ineffable. This interplay between the measurable and the mysterious poses a crucial question: How can we develop an evidence-based framework to guide the environmental and experiential factors that influence these journeys?

The answer lies in collaboration. Understanding the conditions that enhance both therapeutic, transcendent, and even recreational outcomes, can only be achieved by uniting designers, therapists, researchers, mystics, guides, technologists and all others upholding this community. This collaboration can help bridge the gaps between science, our lived experiences, the environment, and the multidimensional aspects of psychedelics.

Only if we work together can we shape a new era of psychedelic healing and discovery, one that is safe, functional, intentional, and capable of supporting truly transformative experiences.

This is just the beginning of my exploration into the role of design in psychedelics. If you’re a researcher, therapist, designer, or simply curious, let’s connect and keep the conversation going.

-

Hartogsohn, I. (2020). American trip: Set, setting, and the psychedelic experience in the twentieth century. MIT Press.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Roseman, L., Haijen, E., Erritzoe, D., Watts, R., Branchi, I., & Kaelen, M. (2018). Psychedelics and the essential importance of context. Journal of Psychopharmacology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881118754710

Okano, L., Jones, G., Deyo, B., Brandenburg, A., & Hale, W. (2022). Therapeutic setting as an essential component of psychedelic research methodology: Reporting recommendations emerging from clinical trials of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine for post-traumatic stress disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 965641. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.965641

Kaelen, M., Giribaldi, B., Raine, J., Evans, L., Timmerman, C., Rodriguez, N., Roseman, L., Feilding, A., Nutt, D., & Carhart-Harris, R. (2018). The hidden therapist: evidence for a central role of music in psychedelic therapy. Psychopharmacology, 235(2), 505–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-017-4820-5

Gandy, S., Forstmann, M., Carhart-Harris, R. L., Timmermann, C., Luke, D., & Watts, R. (2020). The potential synergistic effects between psychedelic administration and nature contact for the improvement of mental health. Health Psychology Open, 7(2), 2055102920978123. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102920978123

Set and Setting: everything you want to know. (n.d.). Webdelics. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://www.webdelics.com/post/set-and-setting-everything-you-want-to-know